Desert Shenanigans with the Frito Banditos

October 11-13, 2002

My early climbing career was strongly guided by the book Fifty Classic Climbs of North America by Steck and Roper. I’m an unabashed checklist ticker. This book caused me to travel to very different areas of the continent and to strive for the well-rounded climbing skills required to be successful. After many years of chasing these climbs and collecting thirty of them, my interest waned as remaining climbs became more difficult and I turned to other climbing objectives. My desire was rekindled this year by the passion of a new convert. Warren Teissier is now in hot pursuit of these routes and his first three (all done this year) were the same as my first three: Ellingwood Ledges on Crestone Needle, Kor-Ingalls on Castleton Tower, and the Durrance Route on Devil’s Tower.

When Warren proposed Ship Rock, I agreed instantly, as did the Trashman. The Trashman has done 31 50CC’s and I wouldn’t be gaining any ground on him here. Our fourth companion was Homie. Homie is the peak bagger’s peak bagger, but hasn’t been that interested in technical rock climbing lately. This objective would combine these two facets of climbing. That was the group, as we wanted to keep things small and stealthy because the legality of climbing Ship Rock falls squarely into the gray area.

Photo 1: Homie and Ship Rock

Ship Rock is the remnants of a volcanic plug. It consists of dark, crumbly basalt and yellow tuff breccia. The tuff has great friction qualities when at low angle, but the higher angled stuff is covered in thin, rotten flakes and has few cracks. We did see some nice cracks in the tuff, but most of them were incipient.

The Navajo legend says that long ago Ship Rock was once a great bird that rose out of the ground with the entire race of the Navajos on its back. It landed in the desert and that was where the Navajos made their life. The rock does appear to be a giant bird with partially folded wings, as it has one main summit and two slightly lower summits to the north and south – these being the elbows of the bird.

Now the Navajos treat Ship Rock as a sacred rock and frown upon climbing ascents. Actually, it is not known how much they frown on this – reports greatly vary. Heck, the Navajos seem to have no problem with climbers if they have deep pockets. They allowed Clint Eastwood to ascend the Totem Pole for the movie Eiger Sanction. Apparently, for a fee, they can overlook the heretical act of climbing.

It all started with this email from Warren to Trashy and myself:

From: Warren Teissier

Sent: Friday, May 23, 2002 8:44

AM

To: Bill Wright; Trashman

Subject: FW: Ship Rock

Hey, isn't Shiprock supposed to be closed? I just

read a TR on the Camp4 website of a guy who climbed it in Nov 2000. If opened, I

want to climb this thing... Here's the

link:

http://www.camp4.com/morerockart.php?newsid=237

WT

Trashy and I both responded:

From: George Bell

Sent: Friday, May 24, 2002

12:25 PM

To: Bill Wright

Cc: Warren

Teissier

Subject: Re: Ship Rock

I've always

wanted to do this one! Sounds like fun, with rather complex route finding.

Everyone I've heard talk about this route talks about the route finding. I've

even heard that finding the initial gully is not obvious.

I like this

"hide your car well". It's flat as a pancake there with no trees, how do you

hide your car? I suppose there may be some features around (especially within 10

miles). Ideally one could befriend some locals, leave them a case of beer, and

then leave one's vehicle right at their hogan (house). In that old Cameron Burns

article there was some story along these lines, where they drank whiskey with

the local herder and left him a few extra bottles.

-George

From: Bill Wright

Sent: Friday, May 24, 2002 8:44 AM

To:

War n’ Peace; Trashman

Subject: FW: Ship Rock

Let's get it on the calendar! A MUST do! We should drop off most of the climbers and then the last guy (me?) can bike back to the drop-off point. If we can get the vehicle to a reasonable spot within say 10 miles.

Great research, Warren! Now we need the numbers of the police and maybe some ranchers. This is great news. I'm excited.

Bill

Warren soon followed up with this note:

From: Warren Teissier

Sent: Friday, May 24, 2002 8:44

AM

To: Bill Wright; Trashman

Subject: FW: Ship Rock

This message is

from the guy that wrote the TR on camp 4

WT

-----Original

Message-----

From: Colorado Springs Climbing Crew

Sent: Thursday, May 23,

2002 11:03 PM

To: Warren Teissier

Subject: Re: Ship

Rock

Warren-

Ship Rock is an unbelievable climb in a crazy

setting, well worth the trip and the effort. I stayed away from it for a long

time, under the same assumptions that most people are, that it is illegal to

climb due to Navajo restrictions that aren't clear. This is not the case. From what I gather, it's not at all

illegal, and there is no climbing ban.

At least this is what we were told by the local authorities. But several ranch owners in the area

don't like people climbing it, and have trashed vehicles, etc in an effort to

keep people away. Since it is so

secluded it basically comes down to this:

If you hide your car well and don't make a lot of noise, you'll be

fine. I've been down there twice in

the last few years and have never even seen anyone else.

Your best bet is to contact local ranch owners if you're concerned about it. Let them know when you'll be around and they probably won't mind. That being said, it's not illegal and you're not violating anything at all by climbing there. It's more of a PR problem than anything else.

If you want more current specifics, contact the local police in the town of Shiprock, NM and I'm sure they'd be glad to help you out. Hope that helps a bit. When it comes right down to it, you'll more than likely be the only ones out there on the day you climb it. On the other hand, if a disgruntled Navajo wants to trash your car in secret, there will be nobody there to stop him. Kind of a toss of the dice, but I personally won't worry about it too much.

Let me know if you learn anything else about that whole situation. My beta is a few years old, so things could have changed. But I wouldn't bet on it. Good luck, the route is ridiculously fun, and has a great alpine feel to it.

-Dan Russell

Trashy sent the following email, further raising our confidence that it could be pulled off:

From: George Bell

Sent: Friday, May 24, 2002

12:25 PM

To: Bill Wright

Cc: Warren

Teissier

Subject: Re: Ship Rock

Gary Clark told

me an interesting story about doing Ship Rock a couple years ago. He said they

did it in "stealth mode" dressed in brown clothing and even using prearranged

rope tugs instead of belay calls. I don't believe they tried to park their car

anyplace clever, however. They had no problems and didn't see anyone the whole

climb. The next week a friend was driving through the area and stopped in the

town of Shiprock for gas. He asked the attendant "anybody ever climb that thing

anymore?” The gas station worker replied “Oh yeah, there were some people on it

last weekend.” Evidently they weren't as stealthy as they thought; probably

their car gave them away.

-George

This led us to devise a series of bird calls for our climbing commands. The canyon wren call was “on belay”; the hoot of an owl was off belay; the screech of a Raven meant “Falling!” Of course, we didn’t actually use these commands for the obvious reason…No one knew what a canyon wren sounded like.

From: George Bell

Sent: Friday, May 24, 2002

12:25 PM

To: Bill Wright

Cc: Warren

Teissier

Subject: Re: Ship Rock

Actually,

if we pull of Ship Rock quickly, the only fitting encore would be

...

The Totem Pole!

I imagine our streak of lawlessness would soon

end trying to climb that one, though.

-George

Of course this was back in May and even if we had good intentions about contacting the authorities, it never got done. We decided on a clandestine approach. We figured to scout the lay of the land on Saturday and go for the ascent on Sunday. That would make for a long, tiring drive home and serious exhaustion at work on Monday, but we felt it necessary to recon the situation. That felt at least half a day for some other objective. Trashy sent out the following email as a suggestion:

From: George Bell

Sent: Monday, October 07, 2002

4:40 PM

To: John Prater

Cc: Bill Wright, Warren

Teissier

Subject: Re: Ship Rock plans!

Hi Guys,

Mexican

Hat isn't "right on the driving route", but it's not far off (60 miles at most).

Also I think it can be done quite quickly, although I'm not sure how long the

hike to the base takes. Mexican Hat is on the climbingmoab.com web site, and in

the prophetic words of Mike Sofranko: "The criteria for the speed record on this

route is car to summit, both climbers AND the cooler of beer".

I'd be up

for doing "The Hat" Saturday morning.

The old Desert Rock description is

quite exhaustive, it would seem. It is 2 pages long! Also there is a great photo

for identifying the correct starting gully, I don't think you could miss it with

that photo. The 50CC description may also be useful but is much briefer. The

route sounds very complicated, should be a great

puzzle!

-George

From: John Prater

Sent: Monday,

October 07, 2002 4:40 PM

To: George Bell

Cc: Bill Wright,

Warren Teissier

Subject: Re: Ship Rock plans!

I've been quiet

so far, but I'm in. Yes, it would be nice if you guys could pick me up in Golden

if possible.

I was also thinking Mexican Hat is nearby and would not be

too time-consuming to climb (heck, the speed record is 9m45s! - uh-oh, what have

I done - never mind that, Bill). Probably get some fun pictures

also.

John

Now Homie had done it. He planted the idea of a speed ascent of the Mexican Hat. Surely there would be some clumsy and hilarious efforts along these lines. We agreed to head out of town on Friday afternoon, meeting at my house first and then picking up Homie down in Golden, on the way out of town. Also in this final week, we added a fifth climber. Steve Mathias, a former member of our Satan’s Minions Scrambling Club, moved to Albuquerque and fallen out of touch. A random email from an unrelated friend prompted me to chide Steve for never responding to my trip reports. That did it. He responded, I mentioned the secret trip and he was in. He’s not much for correspondence, but the guy is real decisive!

When we met to pack, the first thing Trashy pulls out of his car is an 18-pack of Bud, saying, “Here’s our bribe to climb the tower. Them redskins still like firewater, right?” I just knew we were going to be a bit hit with the natives…

We drove out in Warren’s Suburban, leaving Denver around 5 p.m. Just after crossing the Divide through the Eisenhower Tunnel, we started to discuss where we’d eat dinner. Trashy mentioned the great burrito place in Dillon, but it was generally agreed that is was too early in the long drive to stop. We wanted to get more miles behind us while it was still light out. Warren piped up here and said, “I want to continue because I think the traffic will lighten up once we get past Vail.” I looked out the window, saw the light traffic, glanced at the speedometer, and said, “Yeah, we’re only going 88 mph! When are we going to be able to open it up?” Clearly we had the right man at the helm.

Warren got us to Fruita, Colorado and I took us to Mexican Hat. We found the dirt road leading to the Mexican Hat, drove down it about a mile, found a flat spot and stopped. It was 12:30 a.m. and we needed sleep. We’d find Steve in the morning.

Saturday, October 12, 2002

In the late 70’s there was a renegade group of hardened, experienced climbers out of Arizona that dubbed themselves the Syndicato Granitica. We were a long, long way from guys like this. The one area where we all excelled, the one trait that bound us all together was our ability to not only survive on junk food, but thrive on it. For instance, for breakfast this morning I had Frosted Flakes, War n’ Peace had a cinnamon roll and Homie downed an Otis Spunkmeyer muffin that was so large it came with its own carrying case. We ate KFC on Friday night and Burger King for lunch on Saturday, with cake and cupcake chasers. We ate junk food 24-7. That coupled with our outlaw climbing objective and our first goal of the Mexican Hat, naturally led us to dub ourselves the Frito Banditos. Homie even had a generous supply of Fritos along.

My alarm went off at 6:30 a.m. but I ignored it. The night had been warm. We finally got up around 7 a.m., packed up the gear, and had some Frosted Flakes. We then piled into the truck and drove another mile or so up onto a mesa just below the Mexican Hat. Here we found Steve eating breakfast. It was great to see Steve again as we had hardly talked since our trip to Zion in April.

We threw our gear together, which consisted of just slings, quickdraws, and aiders, and headed up the short approach to the Hat. The Bandito route consists of just six bolts. The first one is driven straight into the bottom of the hat and it is probably nine feet off the ground. I had brought a cheater stick to solve this problem. It was either that or someone was going to have to get on all fours to provide a step up.

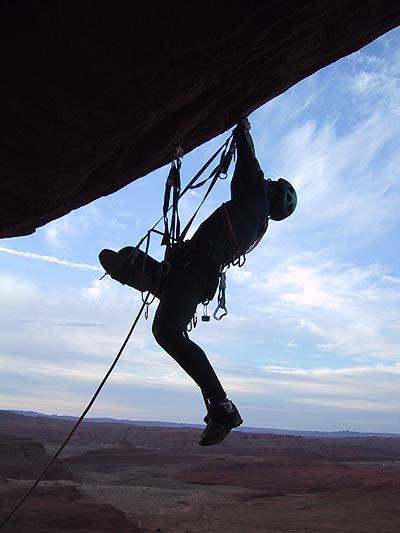

Photo 2: This is me leading the Bandito Route on the Mexican Hat

I led up the route in just seven or eight minutes. For most of the route you’re just dangling under this roof. The reaches aren’t too bad and things go pretty well. I think the crux is probably free climbing past the last bolt, but everything is pretty easy. Steve followed on aiders, as did Homie. Then Trashy led it and Warren followed on aiders.

On the www.climbingmoab.com site someone said they had climbed this route in 9m45s. I thought we could beat that and Steve was game, so I headed up again. This time I took about five and a half minutes to lead the route, still flailing around like a gumby, but doing it a bit faster than the first time. Steve was really fast following on aiders and completed the route in 7m45s – a new speed record[1]!

Trashy said that he didn’t think it was faster to follow the route with aiders. He said jugging should be faster. I was looking for another opportunity to try again and immediately jumped at it. “Let’s go then!” Trashy said, “I already have my harness off.” I give him a look of exasperation and say, “I think we can solve that problem.” Next he says, “I didn’t bring any jugs up here.” It is only a five-minute hike back to the car, but I know that will kill our momentum. Homie comes to the rescue and pulls a pair out of his pack. We’re set! But then War n’ Peace looks impatiently at his watch, probably regretting the day he invited such a hyperactive rapscallion like myself along, and then says, “Bill, it’s already 9:50…” I look at him for a second, not sure if he can be serious, and say, “Warren, the entire ascent is going to take five minutes. I think we can spare the time…”

I moved into position once again with my cheater stick and as I clipped the bolt the clock was started. I did a bit better than last time, but still made some bozo moves. I had trouble with the second bolt and then forgot to unclip myself from the second to last bolt as I started to do the free moves over the lip. Clearly, I’m no Dean Potter.

I was off belay in 4m12s, but had trouble pulling up enough rope to fix the rope as Trashy already had his jumars on the lead line. I fixed the rope by 4m30s and Trashy jugged “like a monkey on speed,” to quote Timmy O’Neill. I hadn’t clipped the first three bolts so Trashy could just jug straight to the rim. I urged him on once he got to the lip with, “Just batman up it! Go, go!” He touched the anchors at 5m33s. Steve’s one and only speed record had lasted for less than ten minutes…

We packed up, hiked down to the vehicles and took off. I rode with Steve in his Saab 9000 Turbo and he believes in using what he paid for. He drives even faster than Warren! In fact, Warren discovered his Suburban had a governor limiting his speed to 100mph. Steve and I pulled into the Burger King in Shiprock at 11:30 a.m. and the others were only five minutes behind us.

After lunch, we headed out to reconnoiter our objective. Six miles south on the Devil’s Highway (666), then eight miles west towards the town of Red Rock, and finally 3.5 miles back north on a bumpy dirt road got us to the base of the behemoth. The mountain looks truly massive up close. The walls are incredibly steep – as steep as any desert tower near Moab, but this baby was five times as high and a thousand times as big. The rock is tuff-breccia and it doesn’t lend itself to cracks easily. We did spy a couple of cool crack systems, but they didn’t touch down or top out.

We hiked north along the west side of the monolith on steep, talus-strewn slopes. When we approached the northwest corner, we headed steeply up hill for a few hundred feet – heading toward the big dark cleft in the mountain. We recognized the start from some photos we carried. We were at the top of a steep slope and it flattened out, but only for about ten feet as the ground ran straight into a cave. There was a nice bivy site ringed with rocks under the overhang. Our route was to turn the overhang on the left. We spent quite a bit of time here trying to boulder out the start. I finally got my feet over the lip but didn’t dare go further for fear of being unable to reverse the moves. It seemed like 5.10 climbing to me. Homie and Steve discovered a possible alternative on the far right side that might go at a low-5th class level, but it also looked dirty and loose and generally unappealing. We’d use it only if necessary.

We continued around Ship Rock, intent on circumnavigating it. Lots of loose dirt and talus scrambling ensued. Apparently Ship Rock is a sacred religious site where the Navajos perform their age-old rituals of trash strewing, beer drinking, and bottle breaking. We were careful not to disturb any of these sacred amulets. I must admit that our little tour had me less concerned about treating Ship Rock as a sacred site.

Back at the truck, I pulled off my bike and rode the 3.6 miles back out to the paved road. I wanted to see how long it took for the ride back in the next morning. At this point we still figured that we’d have to dump the car at a different location so as not to arouse suspicion.

We drove back into Shiprock, the town, and here, for some reason, Steve tried to put some air in his left front tire at a nearby air hose. This only let air out of this tire. The next hour was spent driving around to numerous gas stations and depleting his tire of even more air. He finally gave up when his tire pressure went down to 17psi. We then drove around a bit looking for a good place to bivy without any luck. Finally, we pulled over and geared up for the next day. We didn’t want to do this in town and we wanted to do it while it was still light out. Here Homie dug out the bicycle pump and started pumping up Steve’s tire. With the proof of concept done, he turned the duties over to Steve.

We packed two racks and five ropes. Why five? Well, we had two 60-meter lead ropes as we’d be climbing as two separate parties: Warren and Trashy on one rope and Homie, Steve and I on the other rope. We brought a 120’ and a 20’ section of rope to fix down the Rappel Gully from the Colorado Col. Finally, we brought an old 7mm 60-meter static line to fix across the traverse pitch – just in case it rained and we couldn’t reverse this pitch. We brought two sets of jugs and aiders to re-ascend the fixed lines. We figured we’d just slide them back down the rope and avoid having to carry five sets. Trashy carried a hammer and bolt kit, just in case. We then had clothes, food, water, two digital still cameras, and one digital video camera. Everyone would carry a pack on the route. Our two racks were identical and consisted of a set of stoppers, blue through orange Alien, and #1, #2, and #3 Camalots. I carried six three-foot slings and four quickdraws. This rack turned out to be nearly perfect. I placed every cam, but only a few stoppers. At one point I wished I had two red Aliens, but I love this piece. Warren and Trashy also brought about 8 leaver slings and biners and used most of them when we cleaned and re-enforced the belay stations.

With our packing done, we headed to Farmington for dinner. We were tired of fast food (don’t tell anyone this!) and found the Three Rivers Brew House in downtown Farmington. I recommend this place. Everyone was very satisfied with the food and service and the portions were large. Fully stuffed, we waddled out to the cars and headed back to Shiprock. We had decided, more by default, to just drive back out to Ship Rock itself and bivy there. We didn’t decide on this initially because we figured it must be the Saturday night hangout with all the broken beer bottles around.

We drove clear to where we’d start the hike the next day. Unfortunately, this didn’t give us much level ground. We ended up scattered far and wide in search of a semi-level spot to sleep. I set my alarm and tried to get some sleep.

Sunday, October 13, 2002

My alarm went off at 6:30 the next morning and I was concerned to see overcast skies above. It was cold as well and I promptly put on multiple layers of clothing, including a hat and gloves. Then I ate breakfast sitting in the car. We started hiking at 7:22 a.m. and Homie led us directly to the base of the route in 25 minutes. We geared up and took care of last minute bathroom business before launching up the steep overhang. It was decided that I was lead this first pitch and everyone else would follow it. From there on up we’d climb as separate teams.

Warren put me on belay and I clambered on top of the cheater rocks and reached up for the greasy flat hold. I placed my feet far underneath the overhang and did not feel strong or confident. I made a half-assed effort to deadpoint to the jug and promptly fell to the ground. What’s with that half-assed effort? If you’re going to deadpoint, dammit, deadpoint like you mean it. Everyone else was strong enough to do this move statically. I was the lone weakling. So, why am I leading it? Because the protection on this pitch is a bit illusory. I hit the hold on my next effort and I knew exactly where to get the upper hold. I quickly swung my foot up onto the high, flat edge and was off my arms. I placed a couple of dicey pieces here and moved up a few feet higher to a better placement. I found some edges and went up and left to the top of the steep wall and placed a good piece. I scampered up easy ground to a short steep section around a chockstone equipped with a rappel anchor. A short ways above this was a single belay bolt on a flat ledge. This pitch is rated 5.8 and was, we all agreed (except for Homie, who has power to burn), the hardest section of the entire climb. For a while we were all concerned that if this was 5.8, then what would the three sections of 5.9 high on the route feel like…

Homie came next and climbed strongly up to the top of the headwall. He stopped here and hauled up all five packs and the 7mm line, which wasn’t in any of the packs. Homie, Steve, and I carried small Camelback packs and didn’t have room for this rope inside. Homie wore two of the packs up to my belay and then put Steve on belay. Steve carried another couple of packs up to the ledge. Once Warren was at the ledge, the three of us moved off, still roped, but carrying it over our shoulders, up a hundred vertical feet of easy, loose talus to the base of a steep wall. Here we made a mistake. Instead of climbing up the relatively easy (~5.4) and solid gully on the left, we climbed up a rib near the center of the Black Bowl. This looked reasonable at the time, but the climbing turned out to be very steep, loose, a bit challenging, and downright terrifying. I climbed up a little over a hundred feet and only placed two pieces of gear, both within two feet of each other, and then did a scary, hard (5.8?) move up a sickeningly loose wall. I belayed from a single, apparently solid, orange Alien.

When Homie arrived at the belay, I moved on, unbelayed, to try and find another piece of gear. The climbing remained pretty steep, but the rock was much more solid and, forty feet above, I had a solid piece of gear. I continued up, still unbelayed, to the top of the wall and ended at a rappel anchor.

While this was going on, Trashy had wisely led Warren up the gully to our left. They moved on ahead of us on 3rd/4th class terrain to the final steep wall leading to the Colorado Col. I soloed up after them to shoot some video while Steve finished climbing the headwall. Soon we were all watching Warren lead a moderate 5th class pitch up the wall.

The climbing in the Black Bowl demands care, as almost all the rock looks rotten. Thankfully, while it all looks rotten some of it is solid. Sorting out the difference between the two is crucial and to make things really exciting there are very few protection opportunities. As Trashy followed the pitch, I led up after him. I’d do all the leading for my team. Homie and Steve were capable, but didn’t much care either way and graciously let me take the sharp end.

Trashy led the final pitch to the Colorado Col. This pitch passes a flake on vertical ground. Here he found an ancient, rusted piton and wisely backed it up with an Alien. The rest of the climbing was airy, but easy and he was soon at the Col. As each of us reached the Col we immediately dove into our packs for all our clothing, for a stiff, biting wind greeted us.

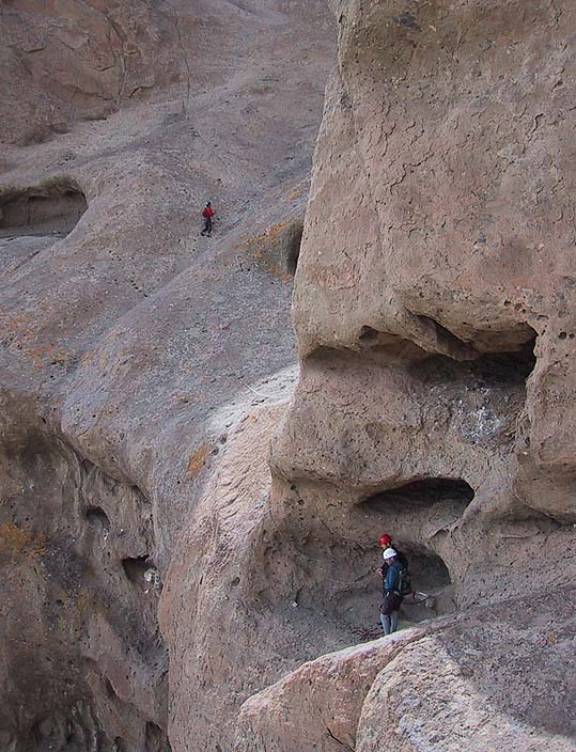

Photo 3: Warren rapping down the Rappel Gully from the Colorado Col.

From here we scrambled down an easy 3rd class gully searching for the rappel anchors. This was intimidating for Warren, as he went first and had no idea when things will roll off and become steep. He soon found the three-bolt anchor and fixed our first rope. He continued down to the next fixed station. This situation is handled in a curious way. The guidebook told us to fix twenty feet of rope down a tight, slightly overhanging chimney system, formed by some large chockstones. The rope ends at the top of a 3rd/4th class, smooth friction gully. There is no talus here at all – it is just like a gully on the Flatrons. This gully is also a bit intimidating to downclimb since the bottom of the gully ends at a precipice. If it started to rain, it would be difficult to re-ascend this gully to your short 20-foot section of rope. I think you should bring two 120-foot sections of rope to fix this descent.

When I arrived at the bottom of this gully, Warren was heading left across a steep, apparently hold-less expanse of rock. This situation here is really quite appalling. There is vertical ground above and below him and the angle of the rock in between is quite steep and smooth. It just seems ludicrous to head out there. This traverse to the upper Honeycomb Gully was discovered via a full day of telescope reconnaissance from the ground and then took two days to work out the sequence of tiny footholds, small finger pockets and overhanging cracks to get it actually climbed. The Traverse Pitch, which is only part of the complete traverse to the giant bowl that is the upper Honeycomb Gully, was 120-feet long. It started off as a level traverse, then went up a ways, and finally a long, descending traverse to a great ledge. Only three bolts and a fixed pin protect this entire distance. Warren did a brilliant job of leading this pitch and correctly finding the right route.

A short, vertical wall now stood in our way. A small piton-scarred crack led through the wall and allowed Trashy and I to place a couple of Aliens. The move here is a tricky, fingery, balance-type boulder problem. It literally lasts for about four feet and the pitch is only twenty feet long itself. It was here that I convinced Warren and Trashy to let me go by and do some route finding of my own. I climbed the 5.9 wall and then continued way left to a small cave with overhanging rock above and below. Here I found two quarter-inch bolts with which to make a belay. When Homie arrived at this point he was flabbergasted. He said, “This can’t be right! Where the heck do we go from here?!” I said, “We go straight left out onto that vertical wall.” “No!” he says. I smile and nod.

Photo 4: Homie following the short 5.9 pitch that immediately follows the traverse pitch.

Indeed, it looks ridiculous, but quickly I’m around the corner and clipping a bolt. Exciting 5.6 ground leads upwards for twenty more feet and I clip another bolt. Here I traverse way to the left on easy ground and then up an easy, but unprotected groove leading up to the huge bowl. I placed a #3 Camalot in a hueco as my only piece of protection in the last sixty feet of easy climbing. I didn’t belay here, though, as it was steep enough to be uncomfortable and I could see things laying back quite a bit just above. I climbed up another twenty feet and braced myself on a couple of good footholds. “Off belay!” I yelled down. I wondered if my companions would balk at such an approach, but I didn’t have much choice and, except for the first twenty feet, the climbing was 5.2 at most.

For most of the climb, I had tried to limit myself to hundred-foot pitches, since both Homie and Steve were tied into our single lead line. I frequently went further than a hundred feet, but never when it would put Homie, who was always in the middle, on challenging ground while simul-climbing.

When Homie and Steve joined me in the big bowl, Steve took over the lead and we simul-climbed up to the horn pitch. We stayed roped together more because we didn’t want to bother with unroping and coiling than anything else, as no gear was placed on this mostly easy terrain. We did negotiate one steep section that was probably 5.4 and I wondered about the wisdom of us all being tied together. Yet I had confidence in my companions. They were both very experienced in soloing exactly this type of terrain on the Flatirons above Boulder. Warren and the Trashman did unrope for this section.

Photo 5: I'm the guy all by myself out on the big slab. I've just led the Double Overhang Bypass pitch and will belay a bit higher. Homie (red helmet) and Steve (white helmet) await their turn to step out over the void.

At the top of the bowl, I led a short easy pitch up to a ledge at the base of the famous Horn Pitch (5.9). There was a solid two-bolt anchor here, so I just brought the others up. The Horn Pitch itself looked intimidating, as it was quite steep and this time for at least forty feet and exposed us almost immediately to 1,800 vertical feet as we crossed from the east to the west side of the mountain. A bolt and three pins protected the lower climbing which was continuously interesting. I ran things out about fifteen feet above the last pin on easier climbing, but it was still steep and the rock looked very suspect here. I was glad to clip the upper bolt that protected the final face moves to the best belay on the route.

We had been spotted from the ground by a couple of vehicles and Warren started to stress about the repercussions to his vehicle. The standard response had apparently been to smash the windows of the cars. I knew all five of us would be financially responsible for any damage to Warren’s vehicle and I figured it wouldn’t cost me more than a couple hundred bucks. Bad to be sure, but not enough to break me and I knew I couldn’t do anything about it now. When I gained the belay at the top of the Horn Pitch, I yelled down to Warren, “I can see your car.” He asked, “Are my windows still intact?” From this height the Suburban was the size of an ant and I couldn’t make out any details, so I merely answered, “It’s surrounded by Redskins!”

Homie followed the pitch, looking solid for a guy who hasn’t done a lot of technical climbing in the past year. Steve also made short work of the pitch and I was soon leading the last challenging pitch – a short pitch rated 5.9. I climbed up over moderate rock to a dead vertical section split by a seam. Here were two solid pins placed about six inches apart. I clipped them both and then fingered the tiny opening above. I could barely get the tips of two fingers into this hole. I had my doubts about pulling off this move. So much so that I explored another alternative to the right, but it wasn’t any easier over there and there wasn’t any protection. The move by the pins was certainly hard, but it was very well protected. I retreated back to the pins and worked out the balancy sequence that made this move seem pretty easy. It was all over in four feet of cerebral climbing.

Photo 6: That's me belaying Homie up the Horn Pitch.

Homie and Steve followed expediently and I was soon leading toward the summit. I knew it was 5.4 ground to the summit and I had summit fever. I told my companions that if things felt easy, we’d just simul-climb to the summit. This is exactly what I did. The climbing was solid and I only clipped the anchors on the next two pitches in going clear to the “piano-sized” summit block. We had done it! I was elated and wanted to let out a loud whoop of joy. In fact, my partners expected this whoop and were a bit surprised when I merely called down, “I’m on top.” I was trying to keep things down in case some unfriendlies were listening down below. Warren and George followed a few minutes later, mainly because Warren got lost in the huge blocks leading towards the summit and had to do an additional belay due to rope drag.

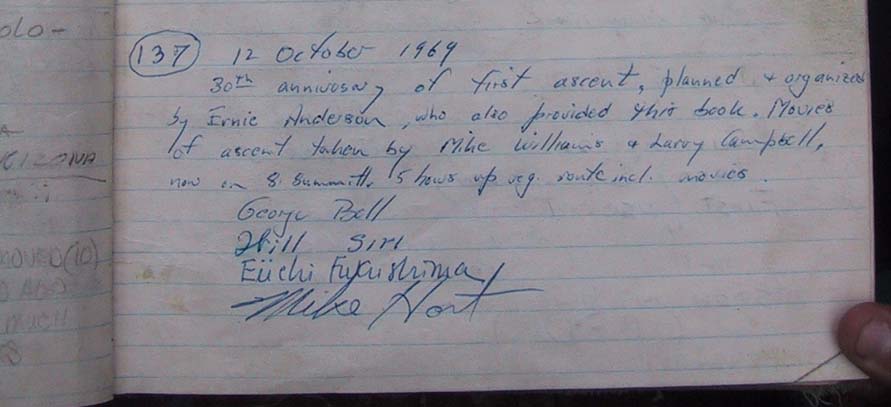

On October 29, 1966 Harvey T. Carter made the first solo ascent in 2h28m. Anyone who records an ascent time to the minute, is my kind of guy. This guy was an early speed climber! We later found in the summit register a notation saying that someone has climbed it solo in 1h59m. The team record, also indicated in the register, was 55 minutes. We didn’t see the actual entry for these speed records, but on the summary page at the front of the book. The summit register itself is fascinating reading. It is a veritable Who’s Who of climbing. Everyone who is anyone has climbed this rock. The sole exception to this is that, much to our dismay, we did not find an entry for Layton Kor. We made the 438th ascent of the mountain (in the 63 years since the first ascent) and only the 5th ascent this year. The last ascent before ours was September 15th – nearly a month ago.

Among the many famous climbers we saw in the register was Harvey T. Carter (many times), George Bell (numerous times), David Brower (first person to lead the traverse pitch), George Hurley, Huntley Ingalls, Paul Stettner, Alex Bertulis, Eric Bjornstadt, Fred Beckey, Dave Rearick (first ascent of the Diamond), Royal Robbins, Pat Ament, Rob Slater, Bill Forrest, Gary Neptune, John Middendorf, Larry Dalke, Paul Piana, Chuck Pratt, Paul Sibley, Allen Steck, Steve Roper, Steph Davis, Bill Briggs, Charlie Fowler (at least a half dozen ascents), Cameron Burns, Gerry Roach and Ray Northcutt. One hilarious entry was by Mugs Stump. It said, “I left Telluride, Colorado at 10:30 a.m. and was on the summit of Ship Rock by 3:30 p.m.” Jim Bridwell did the first ascent of the 1980’s in February, 1980 and in winter conditions, with the upper bowl semi-iced up.

Photo 3: An entry from the summit register.

I was the first one on the summit and the second to last one to leave. I spent 58 minutes on top, enjoying the view, eating, shooting video, and listening to Homie read the register. Finally, around 2:15 p.m. Warren prodded us to get moving. There was a lot of work left to do before we’d be safely on the ground. In the register we read of the 25th anniversary ascent, where Trashy’s dad was one of the party members. They had taken six hours to ascend (compared to our five hour ascent), but an amazing seven hours to descend[2]. That had us a bit concerned.

We did two single rope rappels back to the top of the last 5.9 pitch. From there we did a spectacular, free hanging at times, 200-foot rappel straight down into the upper Honeycomb Gully. We downclimbed the gully to the steep section and then did a low-angle single-rope rappel. Here I took the lead and scouted across a smooth slab to where there should be anchors. Sure enough, there was a rappel anchor there and another single rope rappel led us over the Double Overhang aid pitch and also down the twenty-foot 5.9 pitch to the ledge at the end of traverse pitch.

The Double Overhang pitch looked positively horrendous. It went up an overhanging incipient crack. We only saw one fixed pin here. The first ascent team had climbed this crack and it took them the better part of three days to get it done. Their first day they got to the base of the crack and then retreated all the way to the ground. The next day they re-ascended back to their high point and only gained twelve additional feet before retreating back to the ground again. Finally, they realized a bivy was in order and polished off the lead the next day.

I find it quite interesting that when Robert Ormes’ team first tried to climb Ship Rock they thought about descending from the Colorado Col into the gully where we now fix ropes. They rejected it as a ridiculously convoluted idea with limited chance of success. It turned out that this was the solution. Then David Brower’s team descended to the Double Overhang Bypass section, looked it much like Homie looked at it and rejected it as ridiculous and impassable and instead labored for three days to climb the Double Overhang. Yet again, what was once rejected turned out to be the solution. A single bolt protects this easy pitch and probably could have been done without any protection and in just a few minutes.

I re-led across the traverse pitch, where we had left our 7mm line. Steve followed and belayed Homie, while I reeled in the 7mm line, coiled it, and threw it on my back. While Homie belayed Warren across the traverse, I soloed up to our fixed 20-foot line. I fixed my lead line to the bottom of this rope so that everyone else could batman up to this point. I then slapped on my jugs and jugged up into the overhanging slot. The rope pulled me hard to the right into an impossibly tight slot and at one point I had to just free climb using chimney technique out to the left. It was an awkward struggle, so much so, that I dug into my pack for a #3 Camalot and fixed it under the chockstone so that the others wouldn’t have to fight the constriction quite so much.

I headed up to the next rope and jugged that as well. Once I was on top, I slid the jugs down the rope to Steve, who had slid his jugs down the 20-foot line to Warren. Steve jugged the 120-foot line dragging one of the 60-meter ropes. We then waited a bit for the second 60-meter line to arrive and we hauled that up. While doing all these Steve knocked off one rock and I knocked one as well. Both rocks were half the size of a baseball. We yelled rock of course. They hit in the talus section at the end of the first fixed line and started more rocks moving. Homie at this point below the chockstones jugging and was none too thrilled with the situation. I think he was pelted with rocks when he was batmanning the line up to jug as well. He was understandably pissed off.

Knocking down rocks is almost always a lapse in being careful. We were very attune to this almost all the time. During the course of hauling up two ropes and dropping down three sets of jugs, while perched at the edge of a cliff and standing on loose talus, we made two small mistakes. Everyone is certainly stressed at times, but it is important to remember that we aren’t trying to be careless. Whenever I yell “Rock!” I know I am really yelling, “I screwed up and put my friends in danger!” You think I like yelling that? You think I go on about my business in the same way after yelling that? I don't. In times of stress the ones being bombarded can yell obscenities and I don't blame them in the heat of the moment - I've done the same. I just wish when things calmed down that apologies are said. I apologized to Homie when he got to the top of the jug and he didn't respond. I love adventuring with Homie, but I wish he had said something back to me...

While Steve went off to explore our descent from the Colorado Col, I fixed the other 60-meter line so that two people could jug at once. Warren was halfway up when Homie started up and once Warren gained the top, I slid his jugs down the free line to Trashy.

Warren and then Homie continued up to the Colorado Col and then down the short fixed line to the “immovable guide’s anchor” just above the Sierra Col. I stayed behind to coil both the fixed lines and help Trashy pack up the gear. We then climbed up to the Col and lowered the second 60-meter line down to Steve and the others. They set up a spectacular 200-foot mostly free hanging rappel down into the Black Bowl. In turn all five of us rappelled down into the loose Bowl. Trashy and I pulled and coiled the ropes and joined the others at the rappel station at the top of the rotten cliff that my team had climbed. Another 200-foot rappel here got us down into the loose talus section. Once again Trashy and I pulled and coiled the ropes. We descended to the top of the first pitch where Warren had backed up the anchors with some fresh webbing. I should note that at most of these rappel stations Trashy, Warren, and Steve were cutting away tons of old webbing and replacing it with new webbing. One final single-rope rappel, our ninth of the descent, deposited us back at our gear.

Photo 7: Homie starting the 200-foot rappel into the Black Bowl on our descent.

I was quite happy to pry off my climbing shoes and my feet were down right thrilled. Much jubilation ensued. We had climbed a big, complex mountain and gotten back down safely. It gives me such a great feeling to be so totally confident with my team members. Knowing we are a team in the truest and most rewarding sense of that word. That is beyond question the greatest joy I get out of climbing – followed closely by the joy of removing my shoes after being crushed for nine hours!

I wondered if this was the hardest mountain I’d ever climbed. I think it is. Some desert towers are tougher, but they aren’t really mountains. I’ve climbed some hard routes in the mountains, but they usually had much easier descent routes. We did the easiest route on this mountain and found it quite challenging. Due to its complexity, any climb in this mountain is extremely committing. As an intact team and moving fast it still took us three hours to get back. Imagine the epic should anyone get hurt or bad weather should move in while still high on the mountain…

The history of the first ascent of this mountain is recorded in excellent detail in Eric Bjornstadt’s now out of print Desert Rock guidebook, where he devotes a full chapter to Ship Rock. This rock was the most sought after climbing objective in the country for many years before it was climbed. Many very competent teams were turned back. The route as it now exists is the most brilliant example of route finding I’ve ever seen. The rock on this mountain is suspect in many locations, but I thoroughly enjoyed this ascent and I hope to do it again. I want to climb the South Summit and maybe the forbidding and difficult North Summit.

We did the ascent in about five hours; the descent in just over three hours; we spent an hour on top; and 90-minutes on the approach, de-approach, gearing and de-gearing. We shot 63 minutes of digital video on the ascent and took over a hundred digital photos. It is surely the most documented climb of our lives and the route is certainly worthy of it.

The hike out went easily and the reminiscing was starting in earnest. Everyone was just thrilled with the accomplishment. We drove back into Shiprock and Steve headed home to Albuquerque. We had dinner at KFC and then started the long drive home at 7:30 p.m. Warren got us to Fruita by 11:30 p.m. and the Trashman took over there. Homie took us from the Eisenhower Tunnel to Golden and I drove the last half hour to my house. I got home at 3:30 a.m., slept until 6:30 a.m. and then was up with the kids. While I was away Derek scored a hat trick (three goals) in his soccer game and his team won 6-1. Daniel and the kids trounced me in basketball this morning: 32-8!

Later this morning we received the following email:

From: Chief Smokey Powerplant

Sent: Friday, May 23, 2002 8:44

AM

To: Bill Wright; Trashman

Subject: FW: Ship Rock

Hello senior

Trashy Bandito,

Don't thing your defiling of our sacred ground yesterday

went unnoticed, we know who you are, we know where you are.

It so happens

that we are holding your precious rack hostage. We considered confiscating it

permanently in an effort to stop your "white-man's ways" of defiling our sacred

rocks and mountains.

But, on second thought, we determined that it was

in the best interest of the Navajo nation to trade it for an 18 pack of Bud so

we could drink it at the base of the rock and appease the spirits that your

transgression angered, by leaving the empties strewn about the base of the

wall.

Let me know when and where you want to trade goods.

Chief

Smokey Powerplant

While we were glad to get off so easily, I was confused that this email could be traced back to War n’ Peace himself. Come to think of it, he looks a little Indian to me…

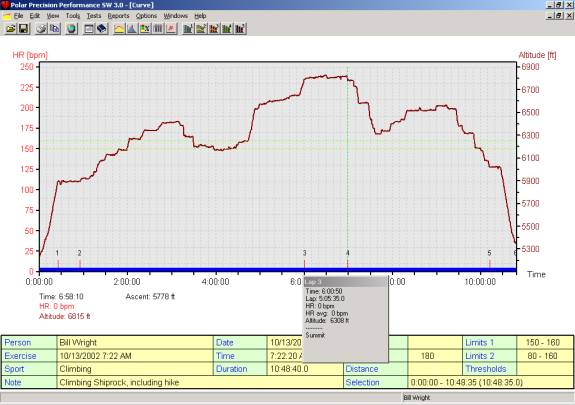

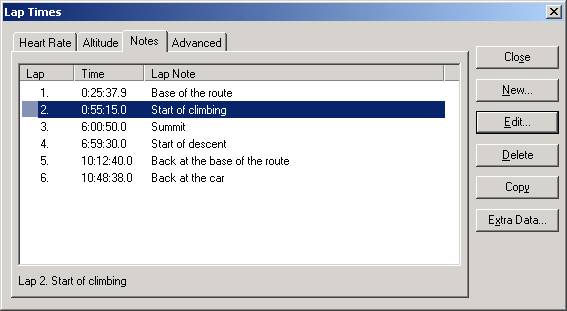

Figure 1: Elevation vs. time for our ascent of Ship Rock. The numbers at the bottom mark our split locations.

Figure 2: Splits for our ascent of Ship Rock