Punks on the Other Side of DenaliBy George Bell (gibell@comcast.net)Written December 1987 [Click on any image for the full size version ~40KB] |

|

|

Denali sunset at midnight from near Wonder Lake

Copyright © 1986 by George I. Bell |

Punks on the Other Side of DenaliBy George Bell (gibell@comcast.net)Written December 1987 [Click on any image for the full size version ~40KB] |

|

|

Denali sunset at midnight from near Wonder Lake

Copyright © 1986 by George I. Bell |

|

|

White Punks on Rope (L to R):

Scott Hartle (air guitar), Joe Terravecchia (vocals), George Bell (crampon). Copyright © 1986 by George I. Bell |

Teenage had a race for the night time Spend my cash on every high I could find Gonna hang myself when I get enough rope White punks on dope WHITE PUNKS ON DOPE

Grunts of resentment and surprise come from the back of the van. We are all worn down by the cramped and noisy conditions; the entire trip has merged into a freakish sequence of driving, dozing, and fueling ourselves and the vehicle. Only now do we realize how strangely appropriate the words to this song are, and from the back of the van come not curses, but spurts of laughter.

In an attempt on any big mountain, it is often the unification of the team members that determines success, rather than the talent of any single individual. The analogy with a musical group is obvious, and we had exploited this to the limits of absurdity. Yes, we are the "White Punks on Rope", brought together not by the usual hash induced haze, but by our common goal of climbing Denali, or right now of finishing this drive. Now starting an Alaskan tour, we have created our own image, complete with song, customized T-shirts and mugs. The dust covered sides of the van are our album cover--at every stop we rejuvenate and add to the graffiti that covers them.

Humor in the face of adversity--a simple concept but effective. Punk #3, Scott Hartle, lurches through the cluttered interior of the van and finally lands in the passengers seat. It is his turn to drive, and in response I lower the volume from its ear--splitting level. Punk #2, Joe Terravecchia, lies snoozing in the back, unconcerned by the beating his new van must be receiving. We have taken one precaution: an evil mesh of fine chicken wire is jury rigged over the windshield, allowing us to pass fearlessly through the cross--fire of gravel bullets that fill the wake of every passing vehicle. It also makes driving difficult, as the eyes can't decide whether to focus on the road or chicken wire. After four hours, I have trouble focusing on anything, and gladly hand the wheel over to Scott.

Talkeetna. Out of the van piles an exhausted and smelly trio. We talk with one of the groups that has just come off. They are in horrible condition, exhausted, smelly, and several sporting nasty sunburns. From the oppressive atmosphere I can tell already that they didn't make it. One guy sits dejectedly muttering about how the conditions were great but the crowd was horrible.

|

|

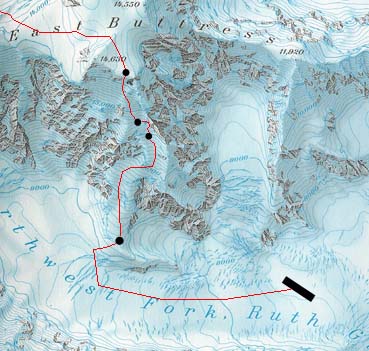

Our route up the East Buttress [Click to see full-sized map] |

Eventually we stop off at the Park Ranger Station to check on our gig. First the mandatory slide show on the terrors of the West Buttress, which quickly has Joe snoring. I gawk dumbly at a large map of Denali on the wall, which has every route marked by a heavy black line. The whole mountain seems trapped under a web of routes. Which one of these lines should we go for? The West Buttress? We have already been warned about the crowds on that thing. From the north, the Muldrow Glacier? Too easy. How about the South Face, Cassin Ridge? Too hard. Finally we are drawn to the east side, where there are relatively large gaps in the tangle of routes. This has always been the most remote and unexplored side of the mountain.

Back in 1954, a team of four Alaskans, including a park ranger by the name of Elton Thayer, had been the first to visit Denali's east side. They began their expedition essentially from Talkeetna, and ended six weeks later at Wonder Lake, completing the first traverse of the peak. Thayer was killed during a fall on the descent of Karsten's Ridge, and the basin east of the summit at 14,000' was named after him. Over the years, several other routes have been done to Thayer Basin, but none of them are easy and it is still rarely visited.

A bold plan was quickly forming. Since the difficulties on the east side start low down, we would be unable to use the standard sled hauling techniques used on most other routes. If we slash weight to the bone, and only carry two weeks of food, we should be able to travel self contained all the way over the top and down the West Buttress. One advantage of the east side is that due to Park Service regulations it sports the closest landing sites to the summit. Thus a rapid, light ascent would seem to be favored. The rangers, though, are skeptical that we will find a pilot willing to land on these seldom visited sites. Although they look reasonable on the map they are sometimes laced by crevasses or covered by avalanche debris. Operating without insurance, any pilot has a lot more to lose than gain from such risky landings.

It seems pretty crazy, really. Not knowing exactly how close we will be able to land, going without skis or snowshoes and with very little food. But it looked like just the thing that might appeal to a bunch of punks. We sign a contract for a two week appearance in the Ruth Amphitheater, and begin packing our instruments.

The next day dawns clear, just like every one before it for

the past week. A continual buzz of glacier planes heads toward the

peak like a veritable swarm of Alaskan mosquitoes. Our own pilot,

Don Lee, promises to land us as high up the northwest fork of the Ruth

Glacier as he can. When we echo the concerns of the rangers, he does not

seem worried at all, and we get the impression he would try to land us

in Thayer Basin were it not illegal. Like most Alaskans,

he has been drawn to the fringes of civilization where natural

dangers are expected, and laws left behind.

|

|

The summit of Denali soars 12,000 feet above the landing site.

Copyright © 1986 by George I. Bell |

The plane snakes through the Ruth Gorge, finally reaching a dead end of immense snow clad walls towering to 15,000'. Spirits are high as the proposed landing site appears flat and free of avalanche debris. But then everyone freezes in terror. An enormous avalanche, no doubt triggered by the noise of the plane itself, has peeled off the rim of the cirque and is bearing directly down on us. Originating a mile above and several miles away from us, it moves in apparent slow motion, but the boiling front is probably a half mile wide and moving at a hundred miles an hour. Panic grips the three climbers in the plane, who are beginning to visualize the consequences of being swallowed up by the approaching maelstrom. Even outside the visible edge it must be stirring up some serious turbulence. With a chorus of "Let's get the hell out'a here!", Don executes a gut wrenching U turn, and soon the killer cloud is settling in our wake.

We return five minutes later to find that the debris has missed our landing site, and after several passes Don sets the plane down. We are ecstatic, as this is about as close as one could legally land. From here the summit is only six miles away, but with 12,000' of relief in between. Wearing sneakers, jeans and a T-shirt, Don is not exactly dressed for glacier travel, but he wants to make sure his take off area is free of crevasses. With Joe and Scott out front in their long underwear and Koflachs, and Don hobbling along behind with a 45 cm axe, they look more like comedians than climbers. Ten minutes later Don's feet are soaking wet, and after reminding us to check out the emergency landing sites in Thayer Basin, he is happy to be airborne once again.

Before the buzz of the plane has died out we get down to business.

Quickly we dispose of an entire cheesecake, six bagels, half a ham and

several cans of fruit. Then we start dinner. For the first day we will

feast on the heaviest and most calorie laden food possible.

After that the cuisine will deteriorate rapidly, dinners consisting

mostly of Minute Rice or Ramen noodles. In fact we soon discover that

due to some packing error several of our dinners do consist entirely

of Ramen noodles. These are given the status of emergency rations.

|

|

The crux of the E Buttress

Copyright © 1986 by George I. Bell |

The lower section of the East Buttress follows a steep ramp which gains more than a vertical mile to Thayer Basin. It is this formation alone which accounts for the unpopularity of this route - for the climbing, although not extreme, is steep enough to preclude sled hauling. On the first ascent of the route in 1963 this section took three weeks, and fixed ropes were put up much of the way. We have trimmed our packs down just enough to move completely alpine style from the start, with no load shuttling. For most of the climb there is nothing worse than 50 degree ice, but even this can be a scary proposition leading with a 70 pound pack. The middle section of the ramp contains a dangerous looking icefall, and we spot a couloir which goes around it.

We decide to do most of our climbing at night because of the better snow conditions. The second night out it begins to snow heavily, and it is the first of several storm bound tent days. Scott creates some memorable sandwiches with the rest of our heavy food--thick slabs of ham and melted cheese between bagel halves. We call them Mac-Kinleys.

Next evening we pack up and quickly ascend the ramp to just below

the icefall. Poking out of a ceiling of clouds are the peaks of

the Ruth Amphitheater, and as the sun rises the scene is unforgettable.

At 12,000', we are already above most of these peaks, but still have more

than 8,000' to go.

|

|

Bergschrund camp (11,800')

Copyright © 1986 by George I. Bell |

We pitch camp in the bergschrund below the couloir. During the day it begins to snow heavily and we have to shovel off the tent continually because of the barrage of spindrift avalanches. Another night is lost to storm. Already we are worried about our limited food supply and go on half rations during storm days.

The next evening finds us climbing the couloir during a storm.

It is not particularly steep but with our heavy packs we must belay.

We all begin to get cold because of the long delays at belay

stances. Scott seems particularly cold and we search desperately

for a ledge large enough for the tent. Finally we arrive at a

ridge crest and begin shoveling out a platform. It seems that we may

be on a cornice, and the thought of a gaping hole suddenly appearing

under the shovel or my feet has me asking for a belay. We become

so worried that we set some anchors in a nearby rock pinnacle and

pass a terrible night lying roped up in the tent on an area so small

we cannot set up the poles.

|

|

Joe and the Punk's Perch

Copyright © 1986 by George I. Bell |

Only the next morning as we move up the ridge do we realize what a precarious spot we slept in. Looking back we see our bivy platform suspended in mid-air, out on an airy cornice which seems glued to a pinnacle on the ridge. From this vantage point, one would not even set foot on that frail platform, which immediately earns the name "Punk's Perch". On up the ridge we see a huge flat area where we soon make camp and start the stoves. We have had little food, water, or sleep in the last 24 hours, and need to recuperate.

Another day of storm, and a morning ritual turns into a game as we all compete for the coveted title "Fastest Dump on Denali". As we each count out the required ten squares of toilet paper we go over the simple rules: First, each contestant is timed from the moment he leaves the tent to the moment he returns, and second, don't cover the evidence. Generously, I allow Joe and Scott to go first so I can plan out my strategy and allow pressure to mount. As their times of 4:38 and 3:54 are carefully logged I notice their technique is riddled with time wasting flaws. Clearly they are not taking this sport seriously! As the starting gate opens I bolt from the tent half naked into a blinding snowstorm. I manage to dodge the clutter of crampons and ice axes, the two steaming mines, and stop before the bergschrund. Shortly I lie gasping on my sleeping bag, while Joe and Scott look at their watches, then each other, and burst out laughing.

"Holy Shit!! It's a new world record: 23 and 3/4 seconds!"

|

|

Hunter on the summit day.

Copyright © 1986 by George I. Bell |

One more day of climbing and we reach Thayer Basin. It is not exactly the beautiful place we had imagined. We navigate by compass in a complete white out, and it's exhausting work for the leader who sinks in eight inches with every step. The distant buzz of a plane immediately reminds us of Don Lee, who would actually consider landing a plane in this hellish place. That evening it begins to clear, and we are treated to a rare close up view of the East Face of Denali. Considering the number of routes on the South Face, it is surprising that this face has never been climbed. We have had our eyes on it the whole trip, and it is time to seriously discuss the possibility.

Several days before we discovered that Scott had minor frostbite on his toes. His feet now get cold very easily and he flatly states that he does not want to risk going to the top. The weather seems unstable and we count only six days of food left. Reluctantly, we all agree that to split the group now would be pushing our luck. Our resources would be spread dangerously thin and Joe and I would have to somehow get back down to Thayer Basin instead of using the West Buttress. Since we are not going over the top, just getting down from Thayer Basin is a major concern. To go down the South Buttress route, the easiest option we know of, we must first climb up 1,500'.

The next morning we begin to do just that. By placing a camp

at 15,800' on the South Buttress, Joe and I can have a reasonable

shot at the summit in a single day of good weather. From here we can

also descend the treacherous South Buttress to Kahiltna Base in a day

or two. In this way we can descend rapidly if Scott's condition

deteriorates, yet still possibly make the summit if the weather improves.

|

|

Foraker from near the summit.

Copyright © 1986 by George I. Bell |

On the crest of the South Buttress, as the wind and snow lash at our frail five pound shelter, we begin a waiting game for a summit attempt. It is sheer torture as we pare down our already slim rations. I take my mind off my stomach with "Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas" while Joe and Scott check the range of our CB. In one hilarious conversation, the White Punks reassure Mabel and Ned, on their way to Fairbanks in a snug Winnebago, that Denali really does exist out there in the fog. Already made suspicious by our weird handle, "White Punks on Rope", Mabel reacts in disbelief when we tell them we are in the middle of a June snowstorm, and we are labeled as hoaxsters.

After two days we are practically down to the dreaded Ramen

noodle dinners, and decide to make an attempt the next morning no matter

what the weather. Scott wakes us at 4 a.m. and cooks us a huge breakfast,

refusing to eat any of it himself. Outside, for a change, conditions

are excellent. It is calm, cold, and has cleared off except for

an endless cloud-bank below us. By looking at which peaks poke through,

we can estimate that the ceiling is around 13,000'.

|

|

Huntington from near the summit.

Copyright © 1986 by George I. Bell |

As we start off, Joe and I quickly realize that this is one of the best summit days of the whole year. The climbing is relatively easy and as the sun rises we can concentrate on the beautiful scene around us. I am soon lost in the rhythmical crunch of crampons and sucking of breath. Our only rival in altitude is the hulking form of Foraker, a gleaming white iceberg adrift in a sea of clouds. Below us lies the Mt. Hunter archipelago, and as the tide lowers further Mt. Silverthorn island appears to our east. On the summit the air practically feels warm because of the lack of wind. We only regret that Scott could not be here to share this moment, and that we did not bring our sleeping bags for a once in a lifetime summit bivouac. Here we talk with the only other people we were to see on the entire climb--a team of Swiss that have just completed the Cassin.

In our state of exhausted euphoria, the descent takes on a dream-like quality, Getting caught by darkness is not a problem here, and the weather, if anything, is improving. Mt. Dan Beard, which towered over our landing site, now lies nearly two miles below us. We reach camp as the last rays of sun are leaving the Moose's Tooth.

Celebration begins immediately with a huge meal and long rest.

The only remaining obstacle is the tricky South Buttress descent; we have

only the vaguest idea where it lies. A whole day goes by before we pack

up and move out onto the South Buttress. It is completely clear and calm

at midnight, as the sun begins its short voyage below the horizon.

To the west lies the Kahiltna Glacier, and beyond the summit of

Foraker glows orange in the final rays. At some unknown point we must

begin our descent in this direction. To the southeast a titanic shadow

stretches over the familiar fingers of the Ruth Glacier. It is the shadow

of Denali, reaching 70 miles out into the swampy lowlands.

|

|

Hunter from 16,500'.

Copyright © 1986 by George I. Bell |

Ahead a lone willow wand pokes through the snow. We discuss the possible significance of this man made feature. It may be a signal for us to leave the ridge. Very unsure of our decision, we begin plunge stepping down the concave powder slope. After four hours of nerve racking traverses under seracs we camp under the South Face near the original base camp for the Cassin Ridge route. It is a great relief to reach this point, for now only an easy glacier walk separates us from Kahiltna Base.

It is so warm down here that we can sunbathe nude on our ensolite pads. We ogle up at Big Bertha, a hanging glacier halfway up the South Face which releases what must be some of the largest avalanches in the world. Our camp is well to one side of the predicted path, but still we are glad that Bertha does not react to our show of skin.

Next evening we reach Kahiltna Base. The traverse has taken us fifteen days, yet we still have two days of Ramen noodles left and a gallon of gas. Even at 2 a.m., this miniature city buzzes with activity. Night is the best time to travel the lower glaciers and a dozen sled hauling enthusiasts start up the West Buttress party route. Our state of consciousness sinks lower and lower as we dispose of the Oreo cookies and case of beer Don Lee kindly flew in for us.

The break up of any successful group is a sad but inevitable

event. For us it happened in Anchorage. The three punks toured

the city, doing all those things we had been craving while on

the mountain. But the movies were boring, the bars not nearly as

interesting as we had anticipated, and there is only so much junk food

one can eat in 24 hours. Scott returned to New Hampshire to nurse his

toes and begin part time carpentry work. Facing car loan payments,

Joe headed to Seward to raise cash by grading fish in a cannery.

I hitched back up to Denali Park and rode the bus out to Wonder Lake.

Despite the fact that I blended in with the friendly tourists, I felt

much more alone then than on the climb.

|

|

Denali from Wonder Lake.

Copyright © 1986 by George I. Bell |

It is rare to find a team so closely matched in ability which is able to get along for long periods under stressful climbing conditions. The mad drive to Anchorage, timing our bowel movements, contacting tourists with our CB--for me these memories were as precious as those of the summit day itself. Above Wonder Lake I trained my binoculars on the north faces of Foraker and Denali, trying to decipher the complicated pattern of buttresses, couloirs, and icefalls. There were still a lot of possibilities in this range, and what about more remote areas in Alaska and around the world that I had never even visited? I began to hope that after tiring of solo efforts, the White Punks might get back together to cut a track up some other beautiful peak.

Postscript: Although Denali's lower East Buttress is technically easier than the Cassin, it has been ascended fewer than 6 times because of the thorny logistical detail that the most difficult climbing lies between 10,000' and 13,000'. This means that sled hauling is out, and a retreat from above this level or a descent of the route would be tricky (although certainly not impossible).

The new route which we wanted to do on Denali's upper east face was finally climbed in 1991 by Lee James and Bob Gammelin (they approached Thayer Basin more sensibly via the lower South Buttress). Those interested in more information on Denali's "lonely side" should consult Jonathan Waterman's guide "High Alaska", and the '64, '88 and '92 American Alpine Journals.

In the Summer of 2000, this article was reproduced with my permission in TRAVELSport Magazine (defunct as of 2013).

In the winter of 2012, my friend

Quang-Tuan Luong took this beautiful sunrise photo of the upper SE side of Denali from Talkeetna.

The north summit is visible on the right.

Notice the prominent triangular buttress in the sun in the middle of the photo, which extends all the way to the right edge.

The left edge of this triangle is the top of the South Buttress route.

The right edge of this triangle is the route we were aiming for which was climbed in 1991 by Lee James and Bob Gammelin.